When I visited a friend’s house, a song called “Pohjois Karjala” by the band Leevi and the Leavings was playing. The song title means “North Karelia.”

“Did you know? Karelia is known as the ‘Sore Point’ or ‘Cherished Territory’ for Finns,”

my friend told me.

“Oh? Karelia…?”

I vaguely knew it was in the southeastern corner of Finland.

But why is this far-off territory such a crucial place for Finns? If you’ve ever been to Finland, you probably know the Karelian Pasty (Karjalanpiirakka). However, few people can pinpoint exactly where Karelia is.

In this article, I will delve into the profound significance of Karelia.

- Why is Karelia so special to Finns?

- Why is it called the “Spiritual Home”?

- Why the Division? | The Dream of “Greater Finland” vs. The Wall of Reality

- The History of Karelia: A Land Caught Between Sweden and Russia

- Finnish National Consciousness and the Epic Poem Kalevala

- World War II and the Evacuation of Karelians

- Karelian Culture: The Fusion of East and West and Inherited Memory

- Summary

- References

Why is Karelia so special to Finns?

Where is Karelia? | A Vast Lake District Spanning Finland and Russia

The Karelia region spans both Finland and Russia. Like Finland, Karelia is an area abundant with lakes.

The name Karelia originates from the Karelian people. Karelians are an ethnic group that diverged from Finns around the 11th century or later, meaning they share a sibling-like relationship with the Finns. The area where the Karelian people lived was originally called Karelia, making its boundaries historically ambiguous.

It is currently defined by administrative divisions.

The Karelia Region and its Historical Territory

While there are current administrative regions (North Karelia and South Karelia) on the Finnish side, the Karelia (Karjala) that Finns hold in their hearts as the “Sore Point” is not limited to these two areas.

It refers to the historical territory that Finland held at the time of its independence, which includes the Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia, both ceded to the Soviet Union during World War II. This is because this land is considered the spiritual homeland of the Finnish nation.

Why is it called the “Spiritual Home”?

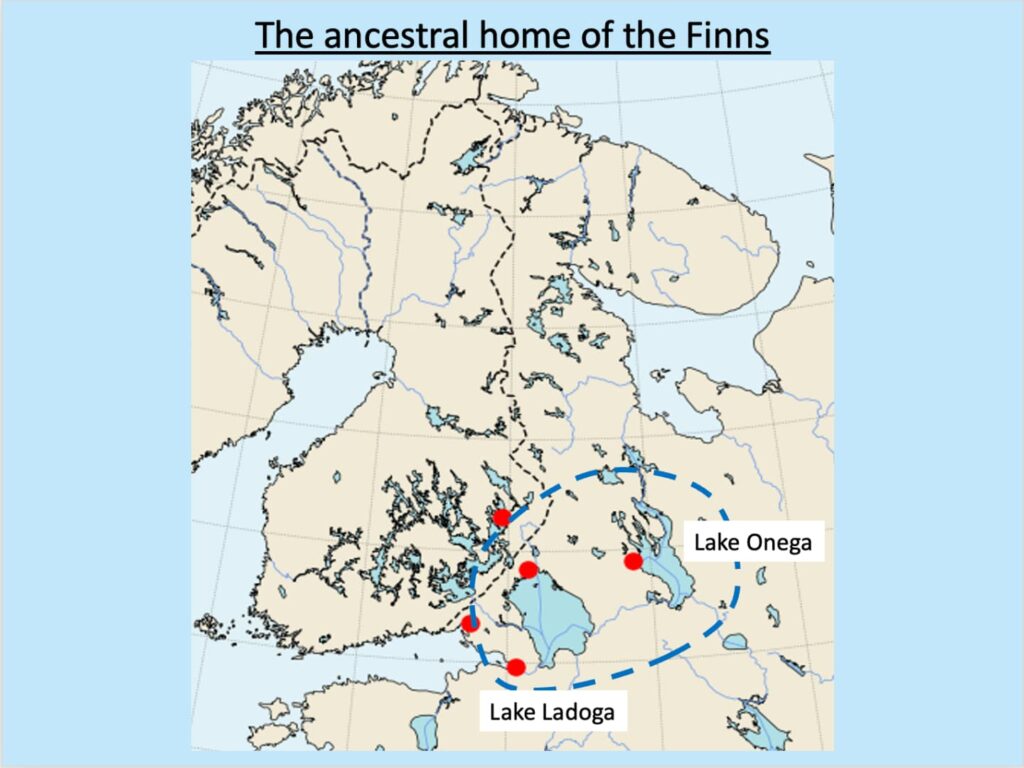

While the exact origins of the Finnish people are uncertain, their ancestors are said to have originated in the area around Lakes Ladoga and Onega. Most of the areas containing these two great lakes overlap with the Karelia region.

The Ancestral Land of the Finns (Around Lakes Onega and Ladoga)

Consequently, the area, particularly around South Karelia, was viewed as the spiritual homeland of the Finnish people. It significantly influenced the rise of Finnish national consciousness during the country’s independence movement. Furthermore, East Karelia, which is currently part of Russia, was considered an area where ancient Finnish customs remained. Immediately after independence, the “Greater Finland” idea, which sought to incorporate East Karelia into Finland, gained momentum. However, East Karelia remained with Russia as the Karelian Republic, taking a separate path from Finland. Why did this division occur?

Why the Division? | The Dream of “Greater Finland” vs. The Wall of Reality

The reason is simple: East Karelia had been consistently within the sphere of Russian culture for a long time.

Basic Information on the Karelian Republic

| Karelian Republic (East Karelia) | Finland | |

| Official Languages | Russian Karelian | Finnish Swedish |

| Capital | Petrozavodsk | Helsinki |

| Main Religion | Russian Orthodox | Protestant (Lutheran Church) |

| Political System | Federal System (Local Administrative Division) | Parliamentary Democracy (Sovereign State) |

| Area | 180,520km2 | 338,431km2 |

| Number of Lakes | Approx. 60,000 | Approx. 180,000 |

Karelia had long been in the Russian cultural sphere. The propagation of the Russian Orthodox faith began around the 11th century and is still practiced there today.

The Greater Finland concept, while fueled by rising national consciousness in Finland, was seen by many as a slightly extreme ideology to incorporate East Karelia and did not garner widespread support.

Let’s now look more closely at the history of Karelia.

The History of Karelia: A Land Caught Between Sweden and Russia

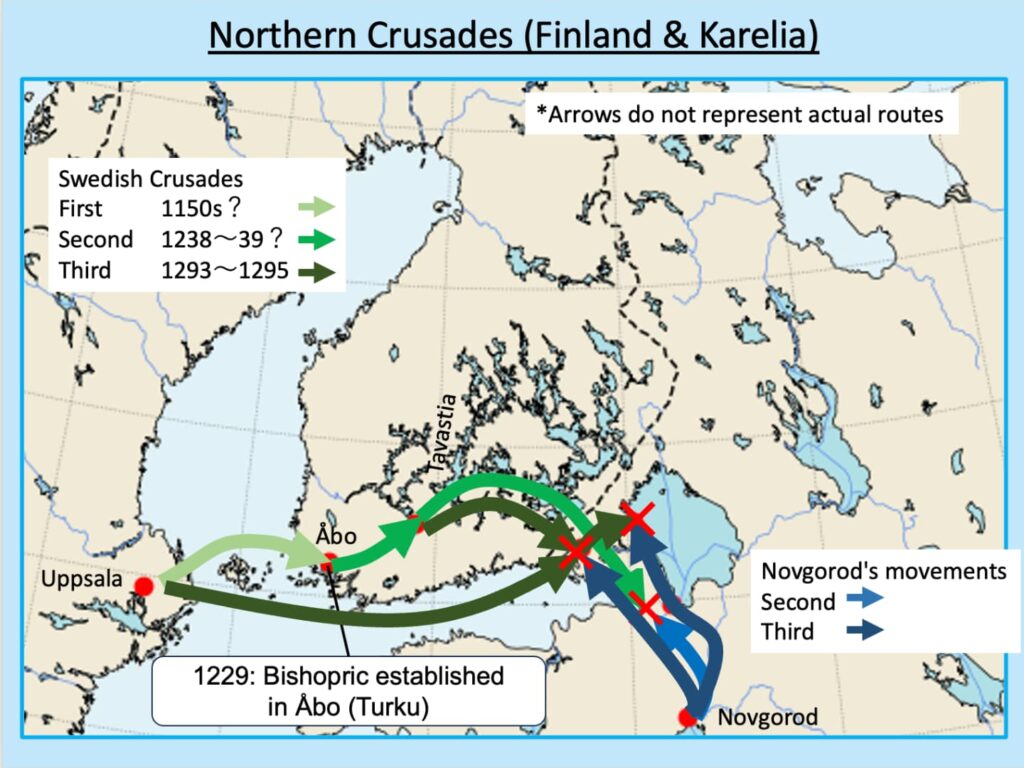

From the 10th century onward, Karelia became the stage for a territorial struggle between Sweden and Russia. Russia desperately sought ice-free ports, while Sweden viewed Karelia as a vital strategic stronghold, serving as a source of tax revenue and a buffer zone against Russia. The conflict intensified particularly from the 12th to 13th centuries. As Novgorod (a predecessor to Russia) sought to advance into Finland, Sweden dispatched Crusades under the pretext of converting heathens.

This sparked a struggle for dominance between Sweden and Russia (whose names changed over time) over the Finnish-Karelian region.

Karelia, in particular, was a region whose rulers and sovereignty frequently changed over the centuries.

| 1323 () | n | Russia (Novgorod) | Sweden | Russia (Novgorod) | Russia (Novgorod) | |

| 1617 () | Swedish Empire | Swedish Empire | Swedish Empire | Swedish Empire | ||

| 1721 () | Swedish Empire | Tsardom of Russia | Tsardom of Russia | Swedish Empire | Tsardom of Russia | Tsardom of Russia |

| 1809 () | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Russian Empire | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Russian Empire | Russian Empire |

| 1812 | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | Russian Empire | |

| 1917 () | Finland | Finland | Finland | Finland | Finland | Russian Empire |

| 1940 () | Finland | Finland | Soviet Union (Provisional) | Finland | Soviet Union | Soviet Union |

| 1944 () | Finland | Finland | Soviet Union | Finland | Soviet Union | Soviet Union |

| Year /Treaty | Finland | South Karelia | Karelian Isthmus | North Karelia | Ladoga Karelia | East Karelia | |||

| 1323 | Sweden | Russia (Novgorod) | |||||||

| Treaty of Nöteborg | |||||||||

| 1617 | Swedish Empire | Tsardom of Russia | |||||||

| Treaty of Stolbovo | |||||||||

| 1721 | Swedish Empire | Tsardom of Russia | Swedish Empire | Tsardom of Russia | |||||

| Treaty of Nystad | |||||||||

| 1809 Treaty of Fredrikshamn | Grand Duchy of Finland | Russian Empire | Grand Duchy of Finland | Russian Empire | |||||

| 1812 | Grand Duchy of Finland (Russian Empire) | ||||||||

| 1917 Finnish Independence | Finland | Russian Empire | |||||||

| 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty | Finland | USSR | (Provisional) | Finland | Soviet Union | ||||

| 1944 Moscow Armistice | Soviet Union | ||||||||

Finland, which was under long-term Swedish rule, miraculously maintained a distinct status even after being incorporated into Russia, which ultimately led to its current independence. However, due to its strategic importance, Karelia was constantly manipulated by the convenience of the great powers. Why, then, was such a place considered the spiritual homeland of the Finnish people? (Details of this history will be introduced in a separate article.)

Finnish National Consciousness and the Epic Poem Kalevala

Karelia is considered Finland’s spiritual homeland because it is the traditional land for the preservation of Finnish culture.

Nationalism and the Compilation of Kalevala

In the first half of the 19th century, the ideology of nationalism, where each ethnic group sought its own nation, became popular in Europe. This ideology reached Finland through students.

At that time, students from Swedish-speaking families were central to the national movement, but emphasizing Swedish heritage under Russian Imperial rule could be seen as an act of rebellion.

Therefore, a movement to foster Finnish national consciousness emerged. One such activity was the compilation of the epic poem Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884).

The Stage for Kalevala‘s Compilation: Why were the Folk Tales of East Karelia Chosen?

To compile the Kalevala, Lönnrot primarily traveled through East Karelia. He believed the words of Z. Topelius, who asserted that Karelia was “the land where the ancient poems and songs still remain.”

The early 1800s may seem sufficiently distant from the modern day, but even then, southern and western Finland were already heavily influenced by Swedish culture, and truly pure Finnish culture was thought to be scarce.

Therefore, Lönnrot traveled extensively through East Karelia, which was particularly isolated from other cultural spheres. (Lönnrot is said to have walked such long distances—a total mileage roughly equivalent to the distance from Finland to the South Pole—that he was considered an excessive walker even in his time.) The Kalevala is a compilation of the poems and songs that Lönnrot transcribed from bards (oral poets). The publication of the Kalevala proved that the Finnish people had an ancient and unique culture.

(↑ You can find videos on YouTube; please listen to the unique rhythm of the Kalevala verse.)

Incidentally, there is also a metal band named Kalevala.

Karelianism as the Spiritual Pillar of the Independence Movement

The publication of the Kalevala drew immense attention to Karelia within Finland. It revealed the very origin of the Finnish nation. Finnish national consciousness grew stronger, and in the late 19th century, art and literature based on the folklore and landscapes of Finland and Karelia flourished.

This movement is called Karelianism. Jean Sibelius’s composition, Finlandia, is one such work, based on the themes of Kalevala and Finnish history. It is famous for being banned by the Russian Empire because it was seen as rousing patriotism.

Thus, Karelia, having suddenly come into the spotlight, was soon to face a time of tribulation.

World War II and the Evacuation of Karelians

The period from World War I to World War II was the most significant time of tribulation in the history of Karelia.

Soviet Security Concerns and the Winter War

Even after Finland’s independence in 1917 and the settling of its internal conflict, tensions with the Soviet Union continued after the border was finalized in 1920.

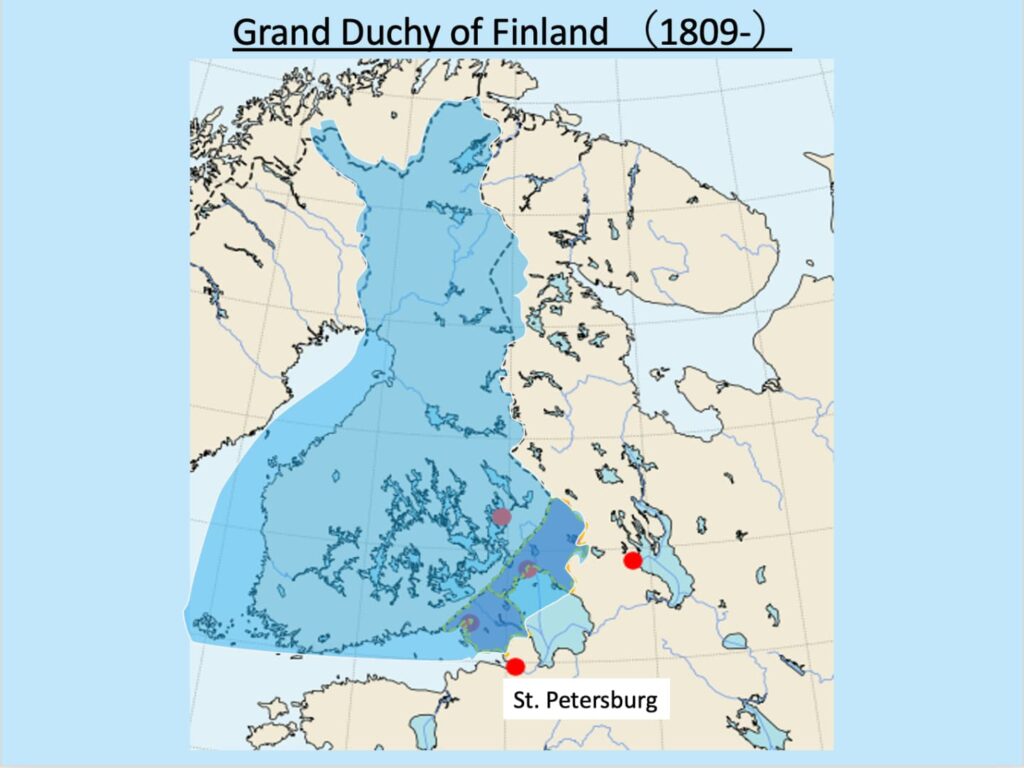

The primary issue for the Soviet Union was that the Finnish border was too close to Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Upon independence, Finland inherited almost all the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Finland.

As a result, Leningrad, which was the Soviet Union’s second capital, was only a few dozen kilometers from the Finnish border. In 1938, Stalin suggested a negotiation, proposing that the Soviet Union would exchange some of its land in East Finland for the Karelian Isthmus. However, Finland could never agree to hand over the Karelian Isthmus, which included the vital industrial city of Viipuri and was a key military stronghold.

When Finland refused, the Soviet Union launched an attack in November 1939 (the Winter War, talvisota), using the pretext of the Mainila shots (a Soviet false flag operation) which supposedly caused Soviet casualties. Karelia became the main battlefield, forcing 420,000 Karelians to evacuate into the interior of Finland. Despite a valiant defense, Finland lost the war to the Soviet Union. The Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia temporarily became Soviet territory.

Evacuation of 400,000 People and the Loss of Home

In the ensuing Continuation War (jatkosota), Finland fought well again. With support from Nazi Germany—the only country willing to assist the resource-strapped Finns—Finland successfully recaptured Karelia. However, once Karelia was recovered, Finland became less proactive in the war. The Soviet Union then redirected the forces they had deployed against Finland to the German front, where Germany eventually lost.

The Soviet Union turned its full attention back to Finland and recaptured Karelia. Although the front lines eventually reached a stalemate, Finland saw no path to victory, leading to the Moscow Armistice in 1944. As a result, the Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia were permanently ceded to the Soviet Union. These two wars led to the massive internal migration of roughly 400,000 Karelians into the rest of Finland.

Karelian Culture: The Fusion of East and West and Inherited Memory

The 400,000 Karelians who lost their homes were forced to bring their entire lives to the interior of Finland. This massive displacement caused Karelian traditional culture to spread throughout Finland, eventually becoming ingrained as part of the national culture.

Karelia was originally a land where the Finno-Ugric cultural sphere and the Russian cultural sphere converged, creating a unique culture. The traditions brought by these displaced people became integral to Finnish cuisine and national pride, serving as vehicles to pass on the memory of their lost homeland.

The Karelian Pasty: Food Born at a Cultural Crossroads

This is best exemplified by the Karelian Pasty (Karjalanpiirakka), the most famous food item from Karelia.

The Karelian Pasty is translated in English as the Karelian pie or Karelian pirogi. Pirogi is a type of baked or boiled dumpling/pastry commonly seen in Eastern European and Russian cultural spheres. While other regions generally use a wheat flour crust, a culture of using a rye flour crust uniquely developed in the Karelian region. The filling was originally made of barley porridge, but as ingredients became available, it evolved over the 19th century to include potatoes and buckwheat, and eventually rice (which was obtained through trade with the East). This pastry, where East and West culinary traditions merged, was traditionally eaten in the Karelia region.

The large-scale post-WWII migration led to its spread across all of Finland. At this time, the version filled with rice milk porridge and wrapped in a rye crust became particularly favored and widely known as the national Karjalanpiirakka. Thus, the Karelian Pasty is a food born from the fusion of East and West cultures in Karelia. Recognizing this cultural background and its uniqueness, the Karelian Pasty is currently certified as a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG) by the EU.

While some cultures, like the Karelian Pasty, spread throughout Finland due to the crisis in Karelia, other traditions are now fading away.

The Tradition of Song and Prayer: Oral Culture Represented by the “Karelian Lament”

Karelia has a traditional oral culture called the Karelian Lament (Itkuvirsi). The Lament was an art form based on improvisation, an expression of deep emotion, and a religious ritual. The song was performed during rites of passage such as weddings and funerals, serving to bid farewell to the deceased and guide their soul. This lament also developed a unique culture, combining the ancient indigenous beliefs of the Finno-Ugric people with the influence of the Orthodox culture from Russia.

As this culture connects the Finns and Karelians with other Finno-Ugric peoples like the Sámi, it is understandable why Finns felt such an emotional pull toward Karelia. However, this tradition is now endangered due to historical changes and modernization in Karelia. I hope that by raising awareness of such regional cultures, we can contribute to their continuation.

Summary

So, how was it? Let’s quickly review the main points.

- The ‘Spiritual Home’ is Historical: The Karelia Finns focus on is the vast historical territory lost during World War II, not just the current administrative regions.

- A Border of Cultures: Karelia was divided between the Western Protestant sphere (Sweden/Finland) and the Eastern Russian Orthodox sphere, making it a crossroads of cultures.

- The Source of National Identity: As the setting for the national epic Kalevala, Karelian culture forms the core of Finnish identity and spiritual heritage.

- Migration and National Food: The massive migration following the wars caused the culturally fused Karelian Pasty to spread throughout Finland, establishing itself as a national food.

Honestly, I’d be happy if, upon hearing the word “Karelia,” you could think,

“Ah! That’s roughly the area!”

Well then, Moikka! (Bye!)

References

- Laitila, Teuvo. “Popular Orthodoxy, Official Church and State in Finnish Border Karelia before World War II.” Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 14 (2000): 49-74.

- 『世界の教科書シリーズ33 世界史のなかのフィンランドの歴史 フィンランド中学校近現代史教科書』 ハッリ・リンタ=アホ、マルヤーナ・ニエミ、パイヴィ・シルタラ=ケイナネン、オッリ・レヒトネン 著、百瀬 宏 監訳 2011 明石書店

- VisitLakelandFinland.com「The Karelian Pasty Workshop」(https://visitlakelandfinland.com/products/the-karelian-pasty-workshop/)2025.11.17アクセス

- Iso-Aho, J., Moilanen, J., Murto, M., Natunen, J. P., Niemi, N., Helppi-Kurki, R., & Vehviläinen, K. (2023). Journeys to South Karelia’Culinary History.

- Wells, C. (2016). Eating Karelia: The geography, history, and memory of Karelian pies. CARELiCA, 2016, 72-82.

- Lind, J. (2000). The Russian-Swedish border according to the Peace Treaty of Nöteborg (Orekhovets-Pähkinälinna) and the political status of the northern part of Fennoscandia. Mediaeval Scandinavia, 13, 100-117.

- Yamaguchi, Ryoko. “なぜ女性は死者と語ることができるのか──カレリアの泣き歌の美学の規則.” 群像社ホームページ, 2018.

- 『トゥオネラの花嫁』ウネルマ・コンカ著 山口涼子訳 2017 群像社

コメント