While researching the Sámi, the indigenous people of the Nordic region, I learned about a ritual called the “Bear Feast.” This bear ritual is a deeply spiritual aspect of Sámi belief and is crucial for understanding the history of the Sámi people.

Background of the Ritual: Sámi and the Bear’s Worldview

Bear Burial Sites Across the Region

Bear burial sites have been discovered in Scandinavia and surrounding areas, including Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Russia.

Especially in areas historically inhabited by the Sámi, bear bones have been found laid out in the same arrangement as when the animal was alive. These bones were discovered in natural caves and beneath rocks—places the Sámi considered sacred, known as Sieidi or Seide, believed to connect the spirit world (Sáiva) with the mundane world.

This custom represents one of the longest-running burial traditions in the Nordic region, spanning from approximately 300 to 1800 AD.

The bear was buried this way because it was considered a creature that embodied regeneration. (I suspect this links to the origins of Santa Claus, which I wrote about previously.)

The Belief that “Bears are Regenerative Animals”

Bears are hibernating animals. While rodents and bats also hibernate, the bear is one of the largest terrestrial animals to do so, often reaching 2 meters in adulthood.

Bears retreat into their dens in winter and reappear on the ground in spring. This cycle was associated with regeneration or reincarnation from the Sáiva (the spirit world, equivalent to the underworld).

As one of the largest terrestrial animals in the North, the bear was also a symbol of physical strength.

Therefore, the bear was seen as a powerful entity, possessing both spiritual regenerative capacity and physical strength. This worldview led to the bear’s revered status. Furthermore, the reasons for worshipping the bear extend beyond this.

Bears as Human-like Beings: Entities that Understand Human Language

Bears stand on two legs and use their front paws like hands.

Their skeletal structure and physical shape resemble humans; they have facial expressions and are believed to shed tears like people. They are omnivores, produce similar excrement to humans, and sometimes even build houses (dens).

Due to these human-like characteristics, the Sámi people believed that the bear could understand human language.

Thus, the bear was seen as a mediator connecting nature and humans, and, by extension, God and humans.

The Dog of God: The Bear

The Sámi regarded the bear as the “Dog of God” (Guds hund) or the “most sacred creature.”

They believed that by obtaining the bear (hunting it), humans could acquire its strength and qualities.

However, bears could not be killed indiscriminately. An appropriate ritual was necessary, and by following this ritual, the Sámi people could gain “lihkku”—a form of luck or prosperity obtained through moral conduct.

The following section details the ritual, showing how motifs such as ‘the brass mark,’ ‘the share of meat,’ and ‘resurrection/regeneration’ from Sámi mythology are enacted in the Bear Feast.

Sámi Bear Mythology

The Sámi bear ritual, the “Bear Feast,” is based on Sámi myths. While several variations exist, here is a summary of the myth recorded by the 17th-century Swedish pastor Fjellström, which was prevalent among the Southern Sámi.

To keep it brief, the key points of the story are:

- A sister, hated by her three brothers, flees into the wilderness and eventually finds a male bear’s winter den.

- The bear takes the woman as his wife, and they have a son, living together as a family.

- Sensing his approaching death, the aging bear tells his wife that he does not wish to continue living.

- The bear instructs his wife to leave footprints in the fresh snow, allowing the three brothers to surround and kill him. He also tells her to place a fragment of brass on his forehead as a mark, preventing his son from mistakenly killing him.

- After the hunters kill the bear, the bear’s son arrives, recognizes his father by the brass on his forehead, and demands a share of the meat. When refused, the son threatens to resurrect the bear by stirring the cauldron violently, causing it to boil intensely. Fearing this, the brothers grant him a share.

(Note: In another version, recorded by Tomasdotter, the wife/sister demands the share of the bear’s meat in point 5.)

Regardless of the version, the key message is that the bear willingly offers its flesh to humans. This narrative establishes the bear as a human ancestor and a being capable of resurrection even after death. These motifs are central to the ritual’s execution.

Details of the Ritual

Hunting and Return Rituals

The ritual involved several taboos.

As mentioned, the bear was believed to be intelligent enough to understand human words and thoughts. Therefore, the Sámi words for “bear” (guovža in North Sámi, duvrie in South Sámi) were forbidden, as they would reveal the hunting intention.

Instead, euphemisms were used, such as kinship terms like áddja (grandfather) or muodd-aja (grandfather with fur), or phrases like puold-aja (old man of the hill) and basse-váise (holy game).

Similar taboos exist among indigenous peoples in Alaska, where they avoid mentioning the animal for fear of being understood. It’s fascinating how similar these hunter-gatherer cultures are, despite the distance.

Preparation for the Hunt: Prayer and Purification

During the period of fresh snow before winter, the hunters marked the location of the bear’s lair and left large, circular footprints around the suspected den.

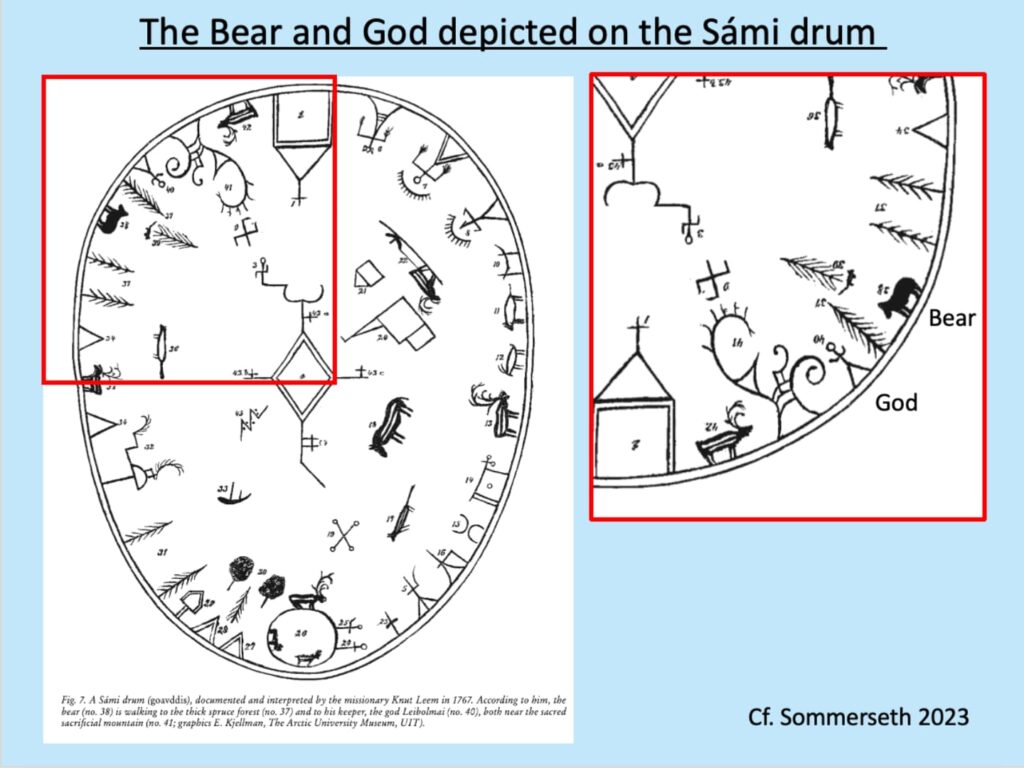

As spring approached, the Sámi shaman, the noaidi, used a Sámi drum to receive a prophecy of a successful hunt from the gods.

Once the date was set, the hunters lived apart from their families for several days, performing bathing and fasting rituals for both physical and spiritual cleansing.

Since the bear is considered an ancestor and a spiritual being, the hunters sought guidance from the gods and purified themselves physically and spiritually before the encounter.

The Hunt: Waking the Bear before the Kill

The bear hunt was performed only after waking the hibernating bear.

It was believed that if the bear’s soul, which wandered outside the body during sleep, did not return to the body before the kill, it would become a dangerous, malevolent spirit. After the kill, the bear was laid to rest at the site for one day.

I interpret this as avoiding disrespect to a spiritual entity by not ambushing it while it slept, but I don’t know for sure.

The Return Ritual: Neutralizing the Bear’s Spiritual Power

The hunters brought the bear back, pulling it with reindeer adorned with brass rings. (The brass was thought to neutralize the bear’s powerful spiritual energy.)

The hunters sang a Vuellie (a type of yoik) to announce their return to the women.

The women waited with their faces covered by linen cloths, forbidden from looking directly at the bear. They viewed it only through the brass rings. They also had to spit chewed alder bark juice (a red sap) onto the returning hunters. This red sap was believed to create a connection with the hunting god Leaibeolmai and had an apotropaic (evil-averting) effect. Finally, the brass rings were attached to the men’s belts.

Upon returning, the hunters had to enter the house not through the main door, but through the back entrance (boaššu).

Perhaps, while the bear still retained its form, its spiritual power was too strong and could negatively affect humans, leading to an exorcism-like process.

Read more about Sámi home structures in my dedicated article.

▶︎ Sámi Dwellings: Structure and Culture

The Feast

The feast took place in a special hut that women were forbidden to enter. Great care was taken to separate the meat from the bones, as the bear’s bones were not to be broken. Only carefully processed meat was permitted for women to eat.

Men ate in the special hut, while women ate in the ordinary dwelling. Women were forbidden from eating specific parts of the bear, such as the blood, heart, and bones. It was believed that if a woman ate the wrong part of the bear, the animal would be enraged and attack during the next hunt.

Realistically, I speculate that the meat parts were divided to prevent negative effects on women who might bear children, but I don’t know for sure.

Purification and Regeneration

After eating the bear meat, the male hunters cleansed themselves by washing their bodies with birch lye. They performed a purification ritual, making bear-like growling noises and running back and forth between the sacred back entrance and the regular door.

After this, the wife of the man who shot the bear would capture her husband and ask when the next hunt would be successful, fulfilling the role of linking the hunting lihkku (prosperity) to the future.

After the feast, the bear’s bones were collected, arranged to match the bear’s original posture, and buried in a pit or beneath a rock. The complete preservation of the bones was believed to be necessary for the bear to grow a new body in the Sáiva and return to the surface as game once again. If a dog took the bear’s bone, the dog’s bone was offered instead.

Finally, the women performed a ritual where they were blindfolded and shot arrows at the bear’s pelt. If a married woman hit the target, her husband would lead the next hunt. If an unmarried woman hit it, a skilled hunter was promised to become her husband.

I wonder, in a Japanese cultural context, if the purification ritual was to both integrate the bear’s spiritual power into themselves and cleanse the defilement of killing a sacred creature. And perhaps the regeneration ritual was a prayer for the success of the next hunt and for their own renewal.

Conclusion and Context

The End of the Ritual and the Decline of the Bear’s Status

The Bear Feast is no longer practiced today. This is primarily due to the Christianization efforts starting in the 17th century, coupled with assimilation policies enforced by governments. These policies compelled the destruction of the noaidi‘s drums and the prohibition of the rituals.

Archaeological research shows that despite these external pressures, such rituals persisted until the early 19th century.

However, as farming and urbanization progressed, and as Sámi society moved away from a purely hunter-gatherer lifestyle, the bear’s perception shifted toward being a harmful animal that threatened livestock. This shift in recognition may also have contributed to the final decline of the Sámi bear ceremony.

It seems that as people moved away from the forest, Japan is also facing a similar bear problem. Though I suppose it’s not that simple!

Bear Rituals and Beliefs in Other Regions

The Sámi were not the only people who performed these bear rituals. Neighboring Karelia also maintained a slightly different “relationship with the bear.”

Bear rituals were once performed in the Finland and Karelia regions as well. In Karelia, in particular, a ritual was performed that involved forming a marriage bond with the bear. This ceremony was intended to appease the dead bear’s soul with alcohol and songs to prevent its revenge.

Interestingly, the red sap of the alder tree was also believed to possess apotropaic (evil-averting) power in Karelian rituals, just as it was in the Sámi tradition. They would use alder wood as fuel to exorcise the bear’s spiritual power (väki).

Furthermore, in Karelia, it was believed that by eating the bear’s powerful organs such as the tongue, eyes, and ears, the hunter could deeply integrate with the bear, acquiring its five senses, shared mind, and even its song.

Comparison of Sámi and Karelian Bear Rituals

| Sámi Rituals | Karelian Rituals | |

| Common Goal | Preventing the bear’s revenge Use of Alder for protection | |

| Key Difference | Focused on the regeneration and survival of the bear and the Sámi community. | Focused on pleasing the bear and achieving deep spiritual unity with it. |

Summary: The Bear Feast and Beliefs

The Sámi Bear Feast was far more than a simple hunting celebration; it was a profound spiritual drama that encapsulated the Sámi worldview.

The ritual was an elaborate system designed to maintain a moral contract with the divine, ensuring that the Sámi received the bear’s strength and physical meat without offending its powerful spirit. By treating the bear as an ancestor and guaranteeing its regeneration through careful burial, the Sámi secured both physical survival and spiritual prosperity (lihkku) for the community. Though the rituals have mostly ceased, the underlying belief in the sacred, regenerative power of the bear remains a cornerstone of traditional Sámi mythology.

References

- Pentikäinen, J. (2015). The Bear Rituals among the Sámi. In E. Comba & D. Ormezzano (Eds.), Uomini e orsi. Torino: Accademia University Press. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.aaccademia.1379(https://books.openedition.org/aaccademia/1379?lang=en)

- Rydving, H. (2023). “The Bear Ceremonial” and bear rituals among the Khanty and the Sami. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe (pp. 677-692).

- Westman Kuhmunen, A. (2015). A Female Perspective on Sami Bear Ceremonies. Journal of Northern Studies, 9(2), 73-94.

- Piludu, V. M. (2023). The Finno-Karelian bear feast and wedding: The bruin as a guest of honour of the village. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe (pp. 723-744).

- Sommerseth, I. (2023). Sámi bear graves in Norway-hidden sites and rituals. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe (pp. 587-602).

- Helskog, K. (2012). Bears and Meanings among Hunter-fisher-gatherers in Northern Fennoscandia 9000–2500 BC. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774312000248

コメント